Princes Bridge

This article was first published in the

White Hat Melbourne

Newsletter No.173 on 19 May 2006.

In that same newsletter you will

find some quiz

questions related to Princes Bridge.

When the first European settlers arrived in Melbourne in 1835 there was

no permanent crossing point of the Yarra River. Over time various punt and

ferry operators set up business but there was still no bridge. In those

times there was no point in waiting for the government in Sydney to provide

a bridge and most of Melbourne�s early infrastructure was provided by

private enterprise. On 22nd April 1840 a private company was set up with the

intention of constructing a bridge across the Yarra.

In our own time, we have become familiar with activist groups in country

towns who agitate for a bypass to be built around their town and then become

surprised that after it is built no-one seems to visit there and spend money

anymore and much of the employment dries up. Things were different in the

1840s. The traders in Elizabeth Street vied with those in Swanston Street to

have the through traffic that would be generated by a bridge.

Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe favoured an Elizabeth Street crossing, but

despite such official pressure the private company favoured the construction

conditions at Swanston Street and it was there in 1840 that they opened

their wooden toll bridge. Until that time William Street had been the de

facto main street of Melbourne since it led down to the docks, Coles Wharf

and the Western Market. With the construction of the bridge, Swanston Street

quickly became regarded as the main street and remained so until recent time

when the city authorities decided it would be a good thing if the

major carriageway should be closed to most traffic but not open up to

pedestrians.

By 1850, the government had caught up and built a fine single span

structure of brick and stone, opened it on 15 November, called it Princes

Bridge, and made it available to the public for free. Little did they know

that within a year, gold would be discovered in country Victoria, there

would be a population explosion, Melbourne would become recognised as �Marvellous

Melbourne� and the narrow carriageway on this fine bridge would become

inadequate for such a bustling city.

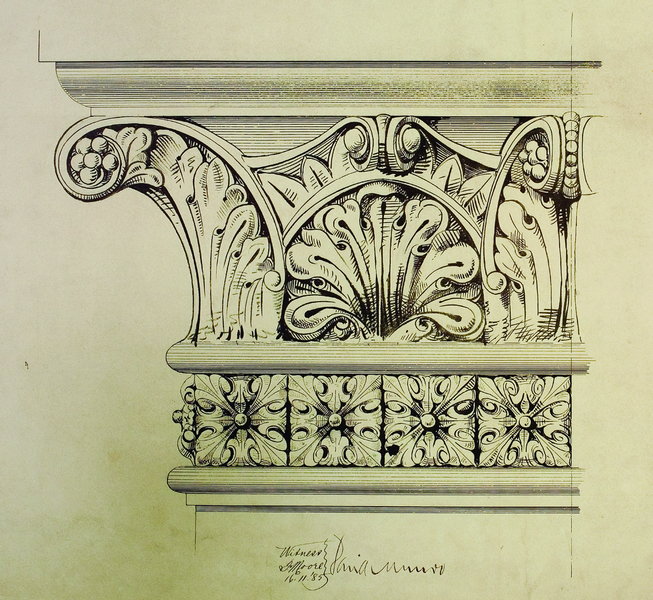

Come 1888 and our second International Exhibition, Melbourne had designed

and built the third bridge on the site and the one that we know today. By

that time the Yarra River had been heavily modified both upstream and

downstream and the major floods of the early years were becoming less

common. In the best Melbourne tradition, the bridge is built on solid

bluestone bulwarks � none of your flimsy Sydney sandstone here � with plenty

of cast iron. Solid yet elegant, befitting the style of the city which had

forced itself onto the international map.

When ex-pat Melburnians in London become homesick they make their way

down to

Blackfriars Bridge and through the mist and the rain pretend that they

are gazing at the structure that helped define the centre of gravity of

Melbourne.

This article was first published under the heading

Melbourne's Hidden Gems in the

White Hat Melbourne

Newsletter No.173 on 19 May 2006

If you make your way across Fed

Square towards Princes

Bridge you will find a set of bluestone steps leading down to river

level. At the base of the stairs is a series of vault-like structures cut

into the bank that have served many purposes over the years � few of which

would be approved of by the polite society crossing the bridge above. In

recent months, this area has been turned into a caf� and wine bar and I

sometimes like to sit there at the end of the day and watch the decades

slowly flowing past. �Would you like some water sir?� asks the

waiter. I remember that Garryowen,

writing at the time of the wooden bridge tells us �Originally the city

was solely dependent on the Yarra water, which was frequently unfit for man

or beast (but) the people of Melbourne had to swallow it, though often

rectified with large dashes of execrable rum or brandy.� �No thank you�

I tell the waiter � �I�ll have a scotch with no water�.

|

From this position at the water�s edge it is possible to see little

huddles of tourists crossing the bridge and pausing to examine the painted

crests on the cast iron lamp posts. That is what their guide book instructed

them to do. At water level, indiscernible shapes float past just below the

water�s surface and I am reminded of Fergus

Humes� description of the place around the time of opening of the new

bridge. �Rats are scampering along among the wet stones, and then a

vagrant dog poking about amid some garbage howls dismally. What is that

black speck on the crimson waters? The trunk of a tree perhaps; no it is a

body . . . floating down with the current. People are passing to and fro on

the bridge, the clock strikes in the town hall, and the dead body drifts

slowly down the red stream far into the shadows of the coming night � under

the bridge over which the crowd is hurrying, bent on pleasure and business.�

Another group of tourists pauses to examine the painted crests. At water

level I am reminded that a century ago that this was the time of evening

that the other rats would gather - the group of street kids who called

themselves the Bourke Street Rats. They could make their way into the centre

of the city, rumble some drunks, then meet up back here next to the bridge.

The place where I am sitting has probably been used a number of times to

divvy up the takings with probably more than the fair share going to the

gang leader � a young thug called Squizzy. At around the same time, Clarice

Beckett gave us probably one of the best paintings of the bridge as seen

from the same position on the other side of the river. The tourists move on

across the surface of the city to their next approved stop.

With the fading light it is time to venture underneath the bridge. The

city lights reflect strange fractal patterns from the river onto the

bridge�s underbelly while the regular rumble of the trams overhead coax the

rivets into a song they have sung for over a century. And sometimes � just

sometimes � at this time you may see shadows and catch snippets of

conversation between the hyperactive 6 year old son of the bridge designer

who wants to know how everything works and the young engineer who has been

employed to work on the bridge while struggling to support his mother and

put himself through university at the same time. The young engineer

patiently explains how the interlocking patterns come together to form a

larger, stronger structure and is immediately bombarded with five more

questions. As I head off along the river I hear

John Monash quietly begin

his next explanation to the young

Percy Grainger.

A bridge can take you more places than just the other side of the river.

|

|

Copyright © 1995 - 2026

White Hat.

|

Other articles in the series Seven Monuments of Melbourne: